The western United States has built their water infrastructure on a melting foundation, and unless we do something about global warming, scientists worry the consequences will be catastrophic.

According to new models, the snow season in states like California could be virtually nonexistent by the end of the century, impacting water supply systems as well as flora, fauna, rivers and even the wildfire season.

If fossil fuel emissions do not abate, researchers predict snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges could decline up to 45 percent come 2050, with low snow or even no snow seasons regularly occurring from then on.

Compared to the past, that’s a dramatic change. Between 1950 and 2000, only 8 to 14 percent of the years were classified as “low-to-no snow”. Yet between 2050 and 2099, that number could reach 94 percent, going from a rare event to one that is expected on a near yearly basis.

Alan Rhoades, a hydroclimate researcher, told the Los Angeles Times that the projections were “shocking”.

“As a kid who grew up in the Sierra, it’s kind of hard to fathom a low- to no-snow future,” Rhoades said.

And he’s not the only one trying to grapple with this potentially disastrous future. Over 70 percent of local water managers believe current water management strategies in the western US are insufficient in light of future climate changes.

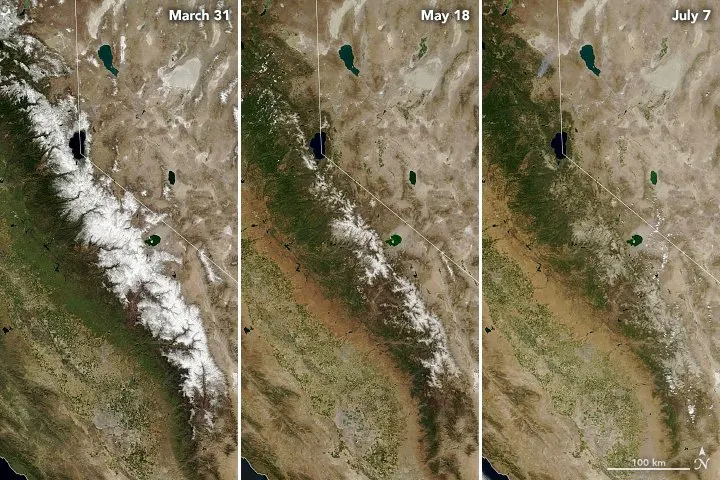

In a usual year, the Sierra Nevada’s snowpack contributes about 30 percent of California’s water. But recently, the state has been experiencing significant episodes of ‘snow drought’.

In the spring of 2021, for instance, the Sierras received only 59 percent of their usual snow water. By May, warm temperatures had reduced that to less than 10 percent. By June, the snowpack was virtually all gone.

How much worse that will get in the future is hard to predict, as yearly snowpacks are based on a complex combination of factors.

Rhoades and his colleagues have therefore created one of the most accurate timelines to date by reviewing all the current studies on future snowpack projections in western states.

Reviewing these data, the authors have found all regions in the western US will experience an “abrupt transition” in snowpack levels after 2050, with back-to-back years of snow drought expected from then on.

The authors defined ‘low snow’ seasons as any year where the snowpack falls below the 30th percentile of the historical peak. Whereas ‘no snow’ seasons are when that number falls below the 10th percentile.

“Therefore, if global emissions continue unabated, there is [about] 35 [to] 60 years before low-to-no becomes persistent across the western US,” the authors conclude.

While the effects are widespread, some mountain ranges will be impacted sooner than others. The Rockies in Colorado, for instance, tend to get their snowfall from cold storms flowing down from the Arctic; while the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges in California receive moisture from the warmer Pacific.

That’s part of the reason why mountains in California will experience a faster and more significant snow decline than other places in the west. Warmer temperatures in this state will lose their snow at nearly double the rate of, say, Colorado.

That’s a serious problem, because snow locks away water, releasing the moisture in the warmest parts of the year, when this resource is needed most.

Rainfall, on the other hand, does not store or release water in the same way, which means current water reservoirs may not be full when we need them to be.

By the late 2040s, if global warming continues at the same pace, researchers predict California’s mountains could experience entire five-year periods of low-to-no snow seasons.

By the 2060s, such years could persist in the Sierras for a decade or more. In other regions of the west, ten year chunks of snow drought likely won’t occur until the 2070s.

“Water storage and conveyance infrastructure was designed and is now managed using spring snowmelt as a central criterion for operations,” the authors write.

“These water management decisions are predicated on the assumption of a stationary climate, which is an unintended yet critical oversight.”

The authors hope their review will be seen as a call to action for policy makers and voters in the western US.

If mountain streams begin to flow more sporadically and water in the soil evaporates at a higher rate, it could drastically change local ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to droughts and fires.

Along with significant reductions in our emissions, the team says we need to implement more thorough water conservation strategies, while investing in infrastructure and desalination plants to cope with future water loss.

Forest management practices could also help create deeper snowpacks by reducing the space between trees.

The good news is that there are solutions; persistent snow droughts in the future are not guaranteed just yet. The current review is based on high fossil fuel emissions right now, which means we still have time to make changes.

The future is not written in stone; it’s packed in ice, and it’s up to us how quickly it melts away.

The study was published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment.