While Goldman's equity analysts chose to lecture their clients about margin compression following a flurry of S&P 500 stalwarts lowering their earnings guidance, the investment bank's economists also warned Monday that stubborn wage pressures are making them "more concerned about the inflationary outlook."

Wage growth is still running at an annualized pace of 5-6% months after generous pandemic-inspired unemployment benefits expired, a stubbornness that has surprised many on Wall Street. Partly as a result, they expect their inflation dashboard to continue to highlight lingering supply chain woes, hot wage growth, strong rent growth, very high year-on-very core PCE and especially core CPI inflation, and very high short-term inflation expectations."

Goldman's team produced charts showing how COVID case numbers have coincided with a rise in the CPI and PCE, two popular gauges of headline inflation, while also breaking down how the costs of "other services" (the most wage-sensitive category) have been the biggest individual driver of price pressures.

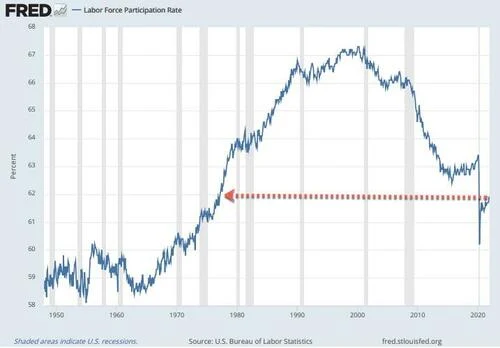

Goldman's team aren't the only ones on Wall Street who are growing increasingly worried about wage inflation. Even the WSJ offered some thoughts on the subject this weekend when it published a lengthy "Weekend Interview" by Mene Ukueberuwa purporting to examine the "Underside of the Great Resignation". As Ukueberuwa quickly points out, the labor-force participation rate in the US has been stuck at 61.9%, 1.5 points below its pre-pandemic level, since August 2020.

Is it perhaps too early to start to question whether the post-COVID "Great Resignation" narrative simply isn't enough? While some bankers might disagree, a growing number of academics and experts have started to question whether structural factors in the US economy might become major impediments in the recovery of the labor market.

For years now, the growing percentage of women in the workforce (women now outnumber men on college campuses, too), and a confluence of other factors like the opioid pandemic and the advent of video-game slacker culture, and the stigmatization of jobs like construction, which require a strong back, but few academic smarts, have caused more and more men to drop out of the workforce. We have been talking about this phenomenon since as far back as 2017.

Nicholas Eberstadt, a political economist at the American Enterprise Institute, was one of the primary proponents of this structural argument in the WSJ essay, which cited his 2016 book "Men Without Book". As he explains, overall labor force pariticpation rate has been declining since 2000, when it peaked at about 67%.

As the rate has fallen, many blamed a growing number of retirees as the Baby Boom generation leaves the workforce. But declines have also been persistent in the population of prime-age people - 25 to 54 - in the workplace.

Eberstadt believes that if the US had maintained the ratio of employment-to-population from 2000, we would have 13M more people working today, more than enough to fill the record number of open jobs.

So, if they're not working, where are all these working-age men and what are they doing? Are they volunteering or channeling their energies into worship or civil society? Not at all. From all we can tell, it looks like they're mostly sitting at home. "By and large, nonworking men don’t 'do' civil society," Eberstadt says. "Their time spent helping in the home, their time spent in worship—a whole range of activities, they just aren’t doing." For a source on this, Eberstadt pointed to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' American Time Use Survey, which compiles respondents’ self-reported habits.

Turns out, working age men were increasingly "staying at home a lot" even before the pandemic. Suddenly, the pandemic has given many who may have been working part-time menial jobs to simply sit home. And inflated asset prices have helped to justify it. Still, there is something "fundamentally degrading" about the workless men of contemporary American society.

"This is not what Marx would have called the 'higher pursuits' of leisure," Eberstadt said. "There’s something fundamentally degrading about this."

Amazingly, Eberstadt also pointed to the fact that the number of working-age Americans receiving federal disability payments has doubled over the past 50 years, rising from 2.2% in 1977 to 4.3% last year.

(Article by Tyler Durden republished from Zerohedge.com)