We've been hearing a lot about interstellar comet 2I/Borisov after its amazing discovery on 30 August 2019. Now the first analysis has hit peer-reviewed publication, landing a description of the comet in the prestigious pages of Nature Astronomy.

If you've been following along, you will be familiar with the findings, posted to preprint server arXiv in September. Long story short? 2I/Borisov is uncannily similar to comets that zoom into the Sun from the outer edges of the Solar System.

But the 'how' part of the study is also really nifty.

The first detection of the comet officially came from Crimean amateur astronomer Gennadiy Borisov, who spotted the space rock with a telescope of his own construction. That part of the story is well known.

What is not as well known is that a team of astronomers led by researchers at Jagiellonian University in Poland spotted the comet independently.

After the surprise detection of interstellar asteroid 'Oumuamua in October 2017 - the first interstellar object known to penetrate the Solar System - astronomers wanted to be ready. So the team created software called Interstellar Crusher to monitor the Possible Comet Confirmation Page, looking for potential interstellar orbits.

On 8 September - just a week after Borisov's detection - Interstellar Crusher got a hit. And, as we all know now, it turned out to be the real deal.

But there's a lot more to a comet than its orbital trajectory, and astronomers Piotr Guzik and Michal Drahus and colleagues got to work characterising our alien visitor, using the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii and the William Herschel Telescope in Spain to take more detailed observations.

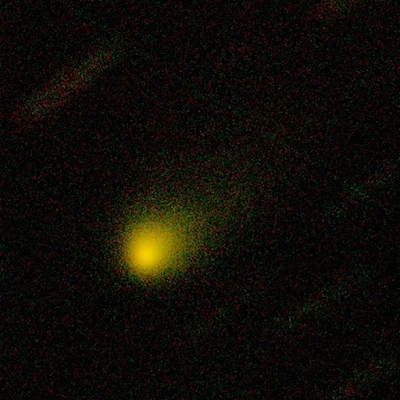

"We immediately noticed the familiar coma and tail that were not seen around 'Oumuamua," Drahus said. "This is really cool because it means that our new visitor is one of these mythical and never-before-seen 'real' interstellar comets."

The team's analysis revealed that the comet is dominated by dust with an extended coma and short tail, and that the nucleus of the comet is around 2 kilometres (1.2 miles across) and unremarkable in shape.

The colour of the comet is mostly greenish, as are the comets that originate in the Solar System, but it is a little redder than the Solar System median.

"Make of this what you will, but based on these initial characteristics, this object appears indistinguishable from the native Solar System comets," Guzik said.

Finding out more about interstellar rocks can tell us what conditions are like in other systems.

If interstellar comets look a lot like our Solar System comets, that means other planetary systems could be made of the same stuff as the Solar System.

So far, we've seen a positive plethora of pre-press papers, and the results are all looking pretty excitingly similar.

An analysis with the OSIRIS instrument found the spectrum of 2I/Borisov was similar to the spectra of Solar System comets, suggesting they have similar chemical compositions.

The comet is releasing cyanide gas, according to a spectroscopic analysis - which is also pretty common to see on Solar System comets. The paper describing that work has been accepted into the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Another spectroscopic analysis confirmed the presence of cyanide gas, and also found diatomic carbon - a gaseous form of carbon often detected in Solar System comets. Cyanide and diatomic carbon are often components that make comets appear to glow green.

One particularly exciting paper has also worked out when and where the comet started outgassing. David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles and Jane Luu of MIT Lincoln Laboratory characterised the dust cloud surrounding the comet, and extrapolated that the comet started releasing gas in June, at a distance of around 4.5 astronomical units - "a typical distance for the onset of water ice sublimation in comets," they wrote.

Finally, another paper, which we touched on last month, calculated where 2I/Borisov may have come from, finding that its origin could be a binary star called 60 Kruger around 13 light-years away.

But this is far from the last we are going to hear about this incredible object.

"The comet is still emerging from the Sun's morning glare and growing in brightness," said astronomer said Waclaw Waniak of Jagiellonian University.

"It will be observable for several months, which makes us believe that the best is yet to come."

The paper has been published in Nature Astronomy.

MICHELLE STARR

If you've been following along, you will be familiar with the findings, posted to preprint server arXiv in September. Long story short? 2I/Borisov is uncannily similar to comets that zoom into the Sun from the outer edges of the Solar System.

But the 'how' part of the study is also really nifty.

The first detection of the comet officially came from Crimean amateur astronomer Gennadiy Borisov, who spotted the space rock with a telescope of his own construction. That part of the story is well known.

What is not as well known is that a team of astronomers led by researchers at Jagiellonian University in Poland spotted the comet independently.

After the surprise detection of interstellar asteroid 'Oumuamua in October 2017 - the first interstellar object known to penetrate the Solar System - astronomers wanted to be ready. So the team created software called Interstellar Crusher to monitor the Possible Comet Confirmation Page, looking for potential interstellar orbits.

On 8 September - just a week after Borisov's detection - Interstellar Crusher got a hit. And, as we all know now, it turned out to be the real deal.

But there's a lot more to a comet than its orbital trajectory, and astronomers Piotr Guzik and Michal Drahus and colleagues got to work characterising our alien visitor, using the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii and the William Herschel Telescope in Spain to take more detailed observations.

"We immediately noticed the familiar coma and tail that were not seen around 'Oumuamua," Drahus said. "This is really cool because it means that our new visitor is one of these mythical and never-before-seen 'real' interstellar comets."

The team's analysis revealed that the comet is dominated by dust with an extended coma and short tail, and that the nucleus of the comet is around 2 kilometres (1.2 miles across) and unremarkable in shape.

The colour of the comet is mostly greenish, as are the comets that originate in the Solar System, but it is a little redder than the Solar System median.

"Make of this what you will, but based on these initial characteristics, this object appears indistinguishable from the native Solar System comets," Guzik said.

Finding out more about interstellar rocks can tell us what conditions are like in other systems.

If interstellar comets look a lot like our Solar System comets, that means other planetary systems could be made of the same stuff as the Solar System.

So far, we've seen a positive plethora of pre-press papers, and the results are all looking pretty excitingly similar.

An analysis with the OSIRIS instrument found the spectrum of 2I/Borisov was similar to the spectra of Solar System comets, suggesting they have similar chemical compositions.

The comet is releasing cyanide gas, according to a spectroscopic analysis - which is also pretty common to see on Solar System comets. The paper describing that work has been accepted into the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Another spectroscopic analysis confirmed the presence of cyanide gas, and also found diatomic carbon - a gaseous form of carbon often detected in Solar System comets. Cyanide and diatomic carbon are often components that make comets appear to glow green.

One particularly exciting paper has also worked out when and where the comet started outgassing. David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles and Jane Luu of MIT Lincoln Laboratory characterised the dust cloud surrounding the comet, and extrapolated that the comet started releasing gas in June, at a distance of around 4.5 astronomical units - "a typical distance for the onset of water ice sublimation in comets," they wrote.

Finally, another paper, which we touched on last month, calculated where 2I/Borisov may have come from, finding that its origin could be a binary star called 60 Kruger around 13 light-years away.

But this is far from the last we are going to hear about this incredible object.

"The comet is still emerging from the Sun's morning glare and growing in brightness," said astronomer said Waclaw Waniak of Jagiellonian University.

"It will be observable for several months, which makes us believe that the best is yet to come."

The paper has been published in Nature Astronomy.

MICHELLE STARR

Tags

Space