Formative forces of water, wind and gravity have fully manifested

themselves in the creation of the Iraqi depression of Gaara. The edges

of this large oval basin near the border between Iraq and Syria rise

several hundred meters in the south and west.

Geologists call the rocks in the lower part of the basin the Gaar formation. They consist of alternating layers of sandstone and soft rocky clay that formed 300 million years ago, when the area covered the shallow sea. Later, carbonate rocks (dolomite, limestone and marl) were layered over the formation, and tectonic forces gradually gave them a domed shape.

The dome reached a maximum height of 30 million years ago. Since then, erosion has been woven into this puff cake. Water, wind and gravity have worn thin carbonate layers in the upper part of the dome, and then dug out the oval depression from the soft and loose rock, leaving more solid carbonates around the edges. These steep slopes along the southern edge played a key role in the expansion of the basin over time. Regular landslides and rock falls, descending on them, forced the southern edge for years to move further to the south.

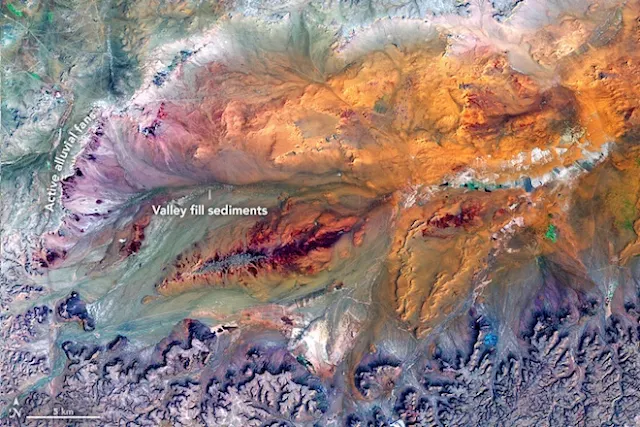

The operational Earth mapper (OLI) on the Landsat-8 satellite received a pool image on August 27, 2017. The snapshot includes data in the shortwave infrared, near infrared and green parts of the spectrum, which makes it easier to distinguish between rock types and soil and to detect the presence of moisture.

Although rains here are rare, during a short wet season, intense outbreaks are possible. Sporadic floods can turn dried canals, known as wadi, into raging rivers that eventually cut out valleys on a limestone plateau along the western and southern edges. When rapid flows enter a relatively flat interior of Gaara, they spread and intertwine into streams with several channels that carry sedimentary rocks over a large area.

As the flow slows down, the sand they carry accumulates along the channels. Over time, the channels migrate forward and backward, creating fan-shaped deposits of sedimentary rock, known as the alluvial cone of the sediment. Some of them, especially along the southern edge, are older and passive; Others, mainly in the west, are smaller and are actively growing.

Although geologists believe that landslides and water currents contributed the most to the formation of this depression, the wind also played a key role. In dry periods, fine sand at the bottom of the basin often rises in the wind and is blown out of it in an easterly direction.

Geologists call the rocks in the lower part of the basin the Gaar formation. They consist of alternating layers of sandstone and soft rocky clay that formed 300 million years ago, when the area covered the shallow sea. Later, carbonate rocks (dolomite, limestone and marl) were layered over the formation, and tectonic forces gradually gave them a domed shape.

The dome reached a maximum height of 30 million years ago. Since then, erosion has been woven into this puff cake. Water, wind and gravity have worn thin carbonate layers in the upper part of the dome, and then dug out the oval depression from the soft and loose rock, leaving more solid carbonates around the edges. These steep slopes along the southern edge played a key role in the expansion of the basin over time. Regular landslides and rock falls, descending on them, forced the southern edge for years to move further to the south.

The operational Earth mapper (OLI) on the Landsat-8 satellite received a pool image on August 27, 2017. The snapshot includes data in the shortwave infrared, near infrared and green parts of the spectrum, which makes it easier to distinguish between rock types and soil and to detect the presence of moisture.

Although rains here are rare, during a short wet season, intense outbreaks are possible. Sporadic floods can turn dried canals, known as wadi, into raging rivers that eventually cut out valleys on a limestone plateau along the western and southern edges. When rapid flows enter a relatively flat interior of Gaara, they spread and intertwine into streams with several channels that carry sedimentary rocks over a large area.

As the flow slows down, the sand they carry accumulates along the channels. Over time, the channels migrate forward and backward, creating fan-shaped deposits of sedimentary rock, known as the alluvial cone of the sediment. Some of them, especially along the southern edge, are older and passive; Others, mainly in the west, are smaller and are actively growing.

Although geologists believe that landslides and water currents contributed the most to the formation of this depression, the wind also played a key role. In dry periods, fine sand at the bottom of the basin often rises in the wind and is blown out of it in an easterly direction.

Tags

Science